Key Facts

- 16.9 million US residents already identify as digital nomads.

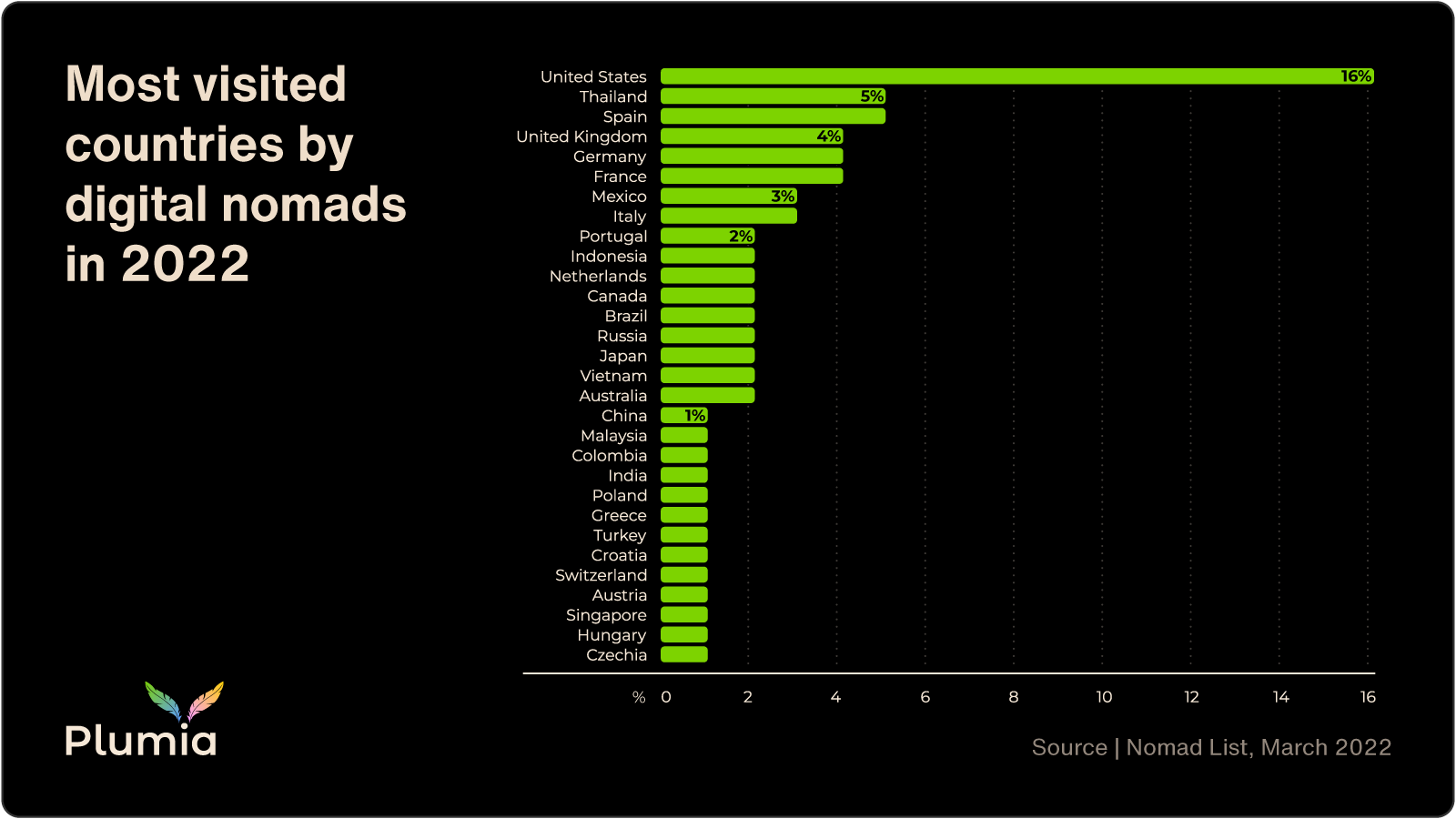

- The US, Thailand, and Spain are the most popular countries for nomads.

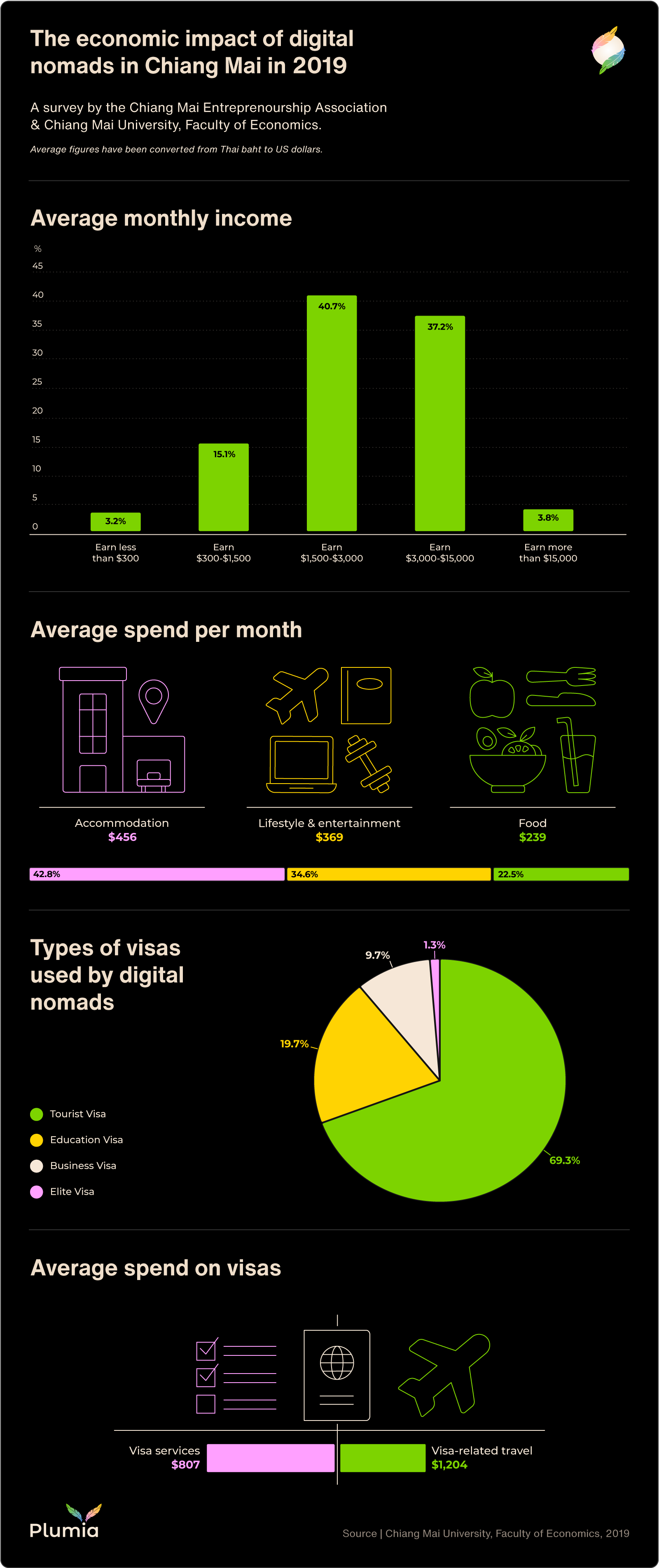

- 86.8% of nomads in the popular nomad hub of Chiang Mai, Thailand travel on a tourist visa.

- The average nomad earns a median salary of $85,000 annually and spends 35% of their income in host communities.

- 60+ countries have introduced nomad visas to date.

Nomads live and move flexibly, which makes it hard to measure their impact on the communities that host them. Currently, an estimated 16.9 million US citizens identify as digital nomads. These people share a love of travel, the ability to work remotely, and a general desire for location independence.

But this diverse group doesn’t traverse the world in predictable patterns. Nomads originate from a variety of countries and work across a range of industries and trades. And because they tend to travel on tourist visas, they’re difficult to distinguish from leisure travelers.

So far, there are few satisfying studies or concrete data on the nomad demographic, but we can make some common-sense assumptions about their contributions to host communities.

Nomads make local economic contributions through spending on food, accommodation, coworking spaces, transportation, and other necessities. Some nomads also pay income taxes if they hold citizenship or residency status and earn income in a place—though norms and policies vary widely by country and visa type.

Nomad List’s State of Digital Nomads 2022 Report is one of few studies that attempts to quantify the economic value of nomads. Its data shows that the average nomad earns a median income of $85k per year and typically stays in one country for eight months. The report also suggests nomads spend at least 35% of their income on food, accommodation, entertainment, and day-to-day essentials.

But nomads’ contribution to host communities goes beyond spending alone. EU policy advisor Cinzia De Marzo believes nomads could accelerate Europe’s digital transformation, and that the experiences they seek can provide a model for sustainable tourism. She explains:

“Thanks to the choices nomads make—such as looking for authentic, sustainable, local and quality-driven experiences—they influence cultural change, and so can become a driver for countries to become more strategic about destination management.”

De Marzo also says that measuring nomads’ contributions could be an important tool for sustainable destination management and economic growth. Though nomads usually fly between destinations, they also tend to travel more slowly than tourists. On the ground, nomads typically rely on public transport systems since they don’t bring their own cars or buy them when visiting countries. In fact, data shows that the average nomad produces 75% less CO2 than the average American.

Though sustainable approaches are key, Victoria University of Wellington Professor Ian Yeoman thinks the nomad mindset can push regenerative-first approaches to tourism further. He says:

“The concept of regeneration goes beyond sustainability, because thinking around sustainability has tended to focus on bringing about carbon neutrality. Regenerative tourism is about visitors making a more positive contribution. Because nomads tend to connect with the community in how they live and travel, they are more aware of the benefits of being local and respecting local sustainability.”

Nomad Hub Thailand: A Case Study

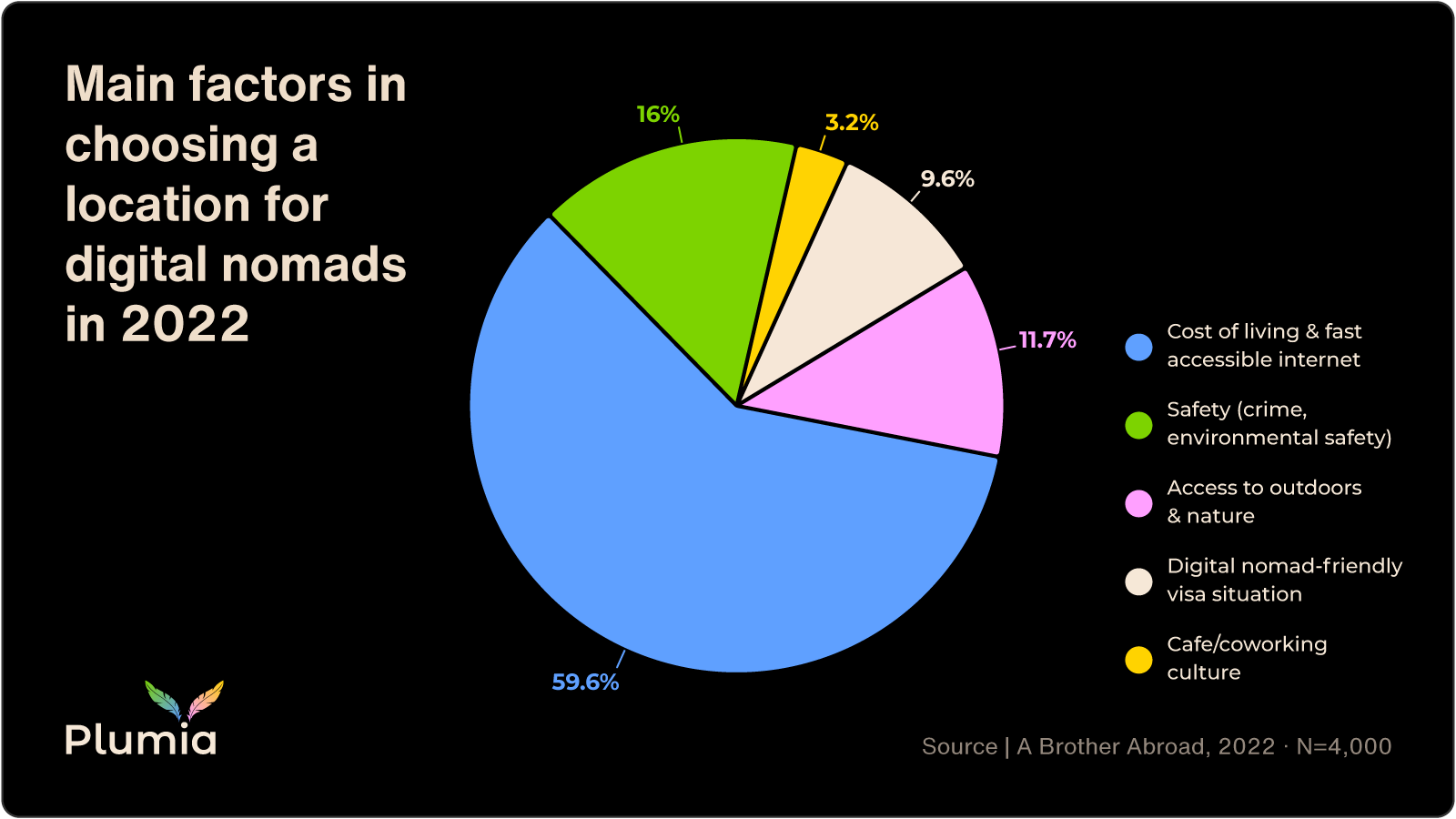

Nomads are defined by their location-independence, though many of them flock to popular hub destinations where there are already strong nomad communities. According to Nomad List, the most popular destinations for nomads are Lisbon, Bali, Chiang Mai, Bangkok, and Mexico City.

According to the State of Digital Nomads 2022 Report, the average nomad:

- earns a median salary of $85,000 per year

- stays in a destination for an average of eight months

- travels on a tourist visa (which means their income isn't taxed locally)

- spends about 35% of their income on the ground

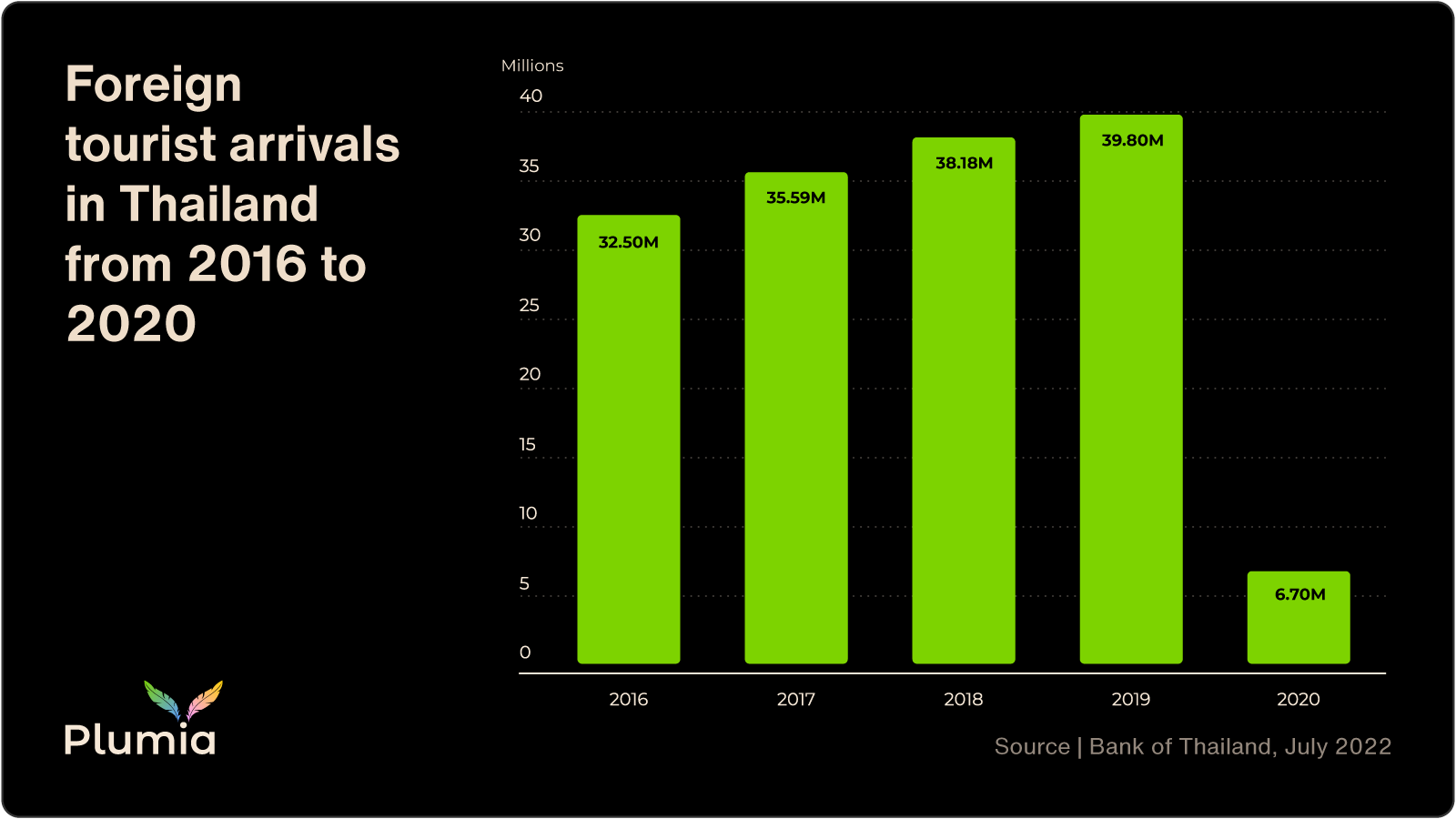

The Plumia team applied these estimates to Thailand, which is home to two of the top five nomad hotspots, to assess the potential economic impact of nomads in the country. Let's say the average nomad spends 35% of their income, equating to $2,479 per month or $19,832 during their typical eight-month stay in Thailand. In 2019, Thailand welcomed nearly 40 million international tourists. If just one million of those visitors were nomads, this would have equaled an economic contribution of $19.8 billion. The GDP of Thailand was $544 billion that year, which means that the expenditure of one million nomads over one year could account for as much as 3.6% of Thailand’s GDP.

A few studies have aimed to gather more precise data on nomads’ local impact. In 2019, Lily Bruns, a startup consultant and global mobility advocate, worked with Dr. Pairach Piboonrungroj of Chiang Mai University, on a survey named “The Capital of Digital Nomads.” They conducted an analysis of the circumstances and impact of 372 digital nomads based in Chiang Mai. Their findings provide a helpful lens for beginning to understand the economics of the nomad movement.

Most nomads (86.8%) surveyed were traveling in Thailand on a tourist visa, showing that most nomads in Chiang Mai are still defined as leisure tourists rather than as nomads or remote workers. The study also found that 40% of the Chiang Mai nomads surveyed earned between $1,380 and $13,830 per month, with an average income of around $7,600 per month.

The research found that nomads spend $415 on accommodation, $218 on food, and $336 on entertainment each month. Added together, the average nomad in Chiang Mai earns $7,600 per month and spends $969 per month on living costs. According to Numbeo, an online database that tracks the cost of living across different destinations, the estimated monthly costs for a single person living in Chiang Mai in 2022 was $499, plus rent, WiFi, and utility costs of around $415 per month.

In other words, nomads in Chiang Mai generally spend a similar amount to locals on the basics of life. Although the sample size was small, this type of research is a step towards understanding the contribution of nomads on a micro-scale.

Piboonrungroj, who led the study, says that they conducted the survey to fulfill a desire—both by Thai locals and internationals—to better understand nomads in Chiang Mai. What surprised him most was the importance of nomads in developing the local creative economy. More than half of the economic production of Chiang Mai’s creative sector comes from people who aren’t formal residents. The study identified a clear pattern of foreign visitors founding creative firms in Chiang Mai and hiring local workers.

We contacted the Tourism Authority of Thailand for this article, and they told us that they held no specific data on nomads in Thailand (though according to one of our sources, the Bank of Thailand has plans to pursue research on nomads in the future). The authorities in Indonesia and Portugal, which have become popular nomad countries in recent years, also told us they hold no specific data on nomads. Even the countries welcoming the most nomads are in the dark about the specifics of this demographic’s economic contribution. As management expert Peter Drucker once said, “[only] what gets measured, gets managed.”

Bruns believes there is an urgent need to standardize the definition of nomad visas so that governments, nomads, and host communities can be sure they're speaking the same language. To help achieve this, she is building a directory and resources for policymakers. She says:

“Thailand doesn’t currently have a specific visa for digital nomads. Many mistakenly refer to programs like the 10-Year Long-Term Residence Visa or the SMART Visa as such. Still, internally the government doesn’t consider these nomad visas, and they don't fit the brief of what nomads actually need. To say Thailand already has one frustrates our advocacy efforts.”

Only a small subset of remote workers and entrepreneurs meet the high-income requirements of the Long Term Residence Visa and the paperwork burden can be off-putting. Even when nomads fit the criteria, they rarely apply for this program, preferring to travel more flexibly with tourist visas.

Nomads and Host Communities

Since June 2020, more than 60 countries have introduced dedicated visas catering to the nomad demographic. These nomad visas allow remote workers with foreign income sources to spend more time in a country than an ordinary tourist visa facilitates, while easier to obtain and imposing fewer restrictions than a traditional work visa.

Nomad visa programs also enable governments to collect tangible data on the nomads who visit their country, helping policymakers understand how their presence impacts host communities. So far, however, each government is crafting its own visa scheme in isolation. As a result, the user experience for nomads is often scattered and inconsistent.

Nomads often want to give back to the communities that host them. Unlike tourists, who only drop in for a week or two, nomads tend to make longer commitments to destinations and are more invested in the success of the places where they live and work. With a nomad visa, governments can start measuring both the soft skills and consumption dollars that nomads bring. This can help policymakers begin thinking about leveraging nomads to help solve problems, support ecosystem development, or share their skills to improve the local economy and provide access to global work opportunities for host communities.

According to Prithwiraj Choudhury, a Harvard Business School Professor, countries need to take the long view:

“Countries and communities need to think about what the most important problems facing the community are and whether digital nomads—who are essentially migrants who can work remotely—can help local communities solve their problems. Smart communities will focus a program on addressing specific issues, whether it’s an aging population in countries like Japan or monetizing natural resources in sustainable ways in the case of places like Chile.”

Choudhury believes the best way to sustain the benefits of digital nomadism is to establish collaborations between nomad visitors and host communities.

Founded in 2010, Startup Chile is a program that grants young entrepreneurs from overseas a one-year visa to work on their companies in Chile. The program offers equity-free capital from the government to budding entrepreneurs, allowing them to accelerate their startup by collaborating with local investors, mentors, and corporates, all while helping to transform Chile into an innovation hub. Within a decade of operation, the program had generated sales of more than $1 billion worldwide. Choudhury says:

“The Startup Chile program shows that collaborations can lead to an awakening of the local innovation ecosystem. Today, Chile has an active startup ecosystem as a result.”

Choudhury goes on to explain that there is more to gain from nomads than consumption dollars alone. Offering local partnerships with global entrepreneurs, and vice versa, offers a runway to longer-lasting rewards.

Ambitious policymakers have noted the success of Startup Chile and are now looking to accelerate innovation in their own communities. As Choudary puts it, the question now is:

“Why have just one Silicon Valley, when we could have a future of startups all over the world?”

Leveraging the Nomad Opportunity

With little concrete data, governments often struggle to design effective policies to make the most of the nomad opportunity. At Plumia, we’re working on mapping the ecosystem and helping policymakers understand the impact of nomads on host communities. Through this work, we’ve come to believe that data and measurement are vital for governments to leverage the nomad oportunity, but it can be daunting to know where to begin.

Here are three simple suggestions for governments seeking to leverage the nomad opportunity:

① Launch a nomad visa

Implement a visa program that allows nomads to stay in a destination for an extended period. This allows for the collection of quantitative data on the number of nomads and their contributions to the local economy such as tax dollars and local spending on food, entertainment, transport, coworking spaces, accommodation, and consumption of other local services.

Crucially, such programs should be co-created with nomads themselves, to ensure alignment between the interests of local governments, host communities, and nomad visitors.

② Offer incentives

Provide incentives for nomads to spend their money locally, such as through discounts at local businesses or reduced tax rates for those who contribute to the local economy. Some countries—like Italy, Spain, and the US—take this further by paying remote workers to relocate to specific towns and cities.

Incentives like this aim to redistribute spending and opportunity away from oversaturated urban hubs towards rural destinations in need of revitalization.

③ Explore local-global collaborations

Support initiatives that encourage skill-sharing and volunteering between nomads and host communities. This can be achieved by funding community projects or setting up programs that match nomads with local organizations that need their skills and expertise. Creating opportunities for local-global collaboration can ease the disconnect between nomads and locals.

For example, coworking space Hubud in Ubud, Bali, Indonesia, hosted various programs connecting nomads and locals for everything from garbage clean-ups to building websites for local schools.

By measuring nomads' contributions to local economies, governments—particularly those with tourism-dependent economies—can start to understand the value of this growing demographic: who they are, what they bring, and how they match with the fabric of the local economy and host community. This can become a blueprint for how nomads can support a more sustainable, holistic, creative, and regenerative approach to welcoming overseas travelers for the long term.

Whether through visas, taxes, consumption, skill-sharing, or volunteering programs, nomads want to integrate and contribute to the places they spend time. Approaching the presence of nomads strategically, governments can identify the potential for partnerships that cross borders and champion innovative solutions that don’t rely on extraction, but regeneration.

About Plumia

Plumia is the moonshot mission to build an internet country for digital nomads and unlock global mobility rights for all.

Through our research and policy work, we provide expertise and insights from our global network of 200k+ digital nomads and remote workers. We also assist governments in shaping policy and designing future-focused solutions around remote work to help grow their local economies.

If you’re a policymaker, government official, or activist interested in the impact and future of the nomad movement, sign up for free email updates from our policy team now: